*Guest post by Julie Gibbons.

This is the third in a series of posts on famous people who did surface design as a sideline to their main jobs. Often, they were so famous that their main job completely eclipsed their pattern-making skills, and it can be hard to find out information about this aspect of their work. So now I would like to reintroduce you to the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Love him or hate him, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) was a man impossible to ignore. Best known as an architect, and particularly known for the wonderful and innovative house Fallingwater, his other works include the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and Ennis House in Los Angeles (appearing in the movie Bladerunner), as well as hundreds of others.

Often surrounded by controversy, he has been considered by many to be brilliant, controlling, outspoken and egotistical. He quarrelled publicly with numerous people and organizations, including the American Institute of Architects, who he very openly chose not to join. They still awarded him the Gold Medal for architecture in 1949.

His work was often featured in many fashionable magazines, such as House Beautiful, and he became very popular. It was on the encouragement of Elizabeth Gordon, the editor of that magazine, that Wright took up the challenge of designing textiles and wallpapers for the home, collaborating with the prominent textile manufacturer F. Schumacher & Co. to produce the Taliesin Line in 1955.

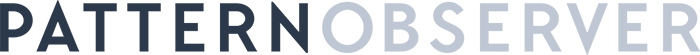

Images via: (Clockwise from top left) Taliesin Line design 105 – Paul Reeves, Taliesin Line design 106 – Birds of Ohio, Taliesin Line design 101 – Art Institute Chicago, Taliesin Line design 102 – Birds of Ohio

It was the only collection of surface designs that Wright ever produced, and while he took the credit, several of the patterns were in fact designed by Schumacher’s staff, guided and approved by Wright. Accompanying the surface designs was a collection of furniture made by Heritage-Henredon, and a paint colour collection produced by Martin-Senour paints, all marketed under the Taliesin Line banner.

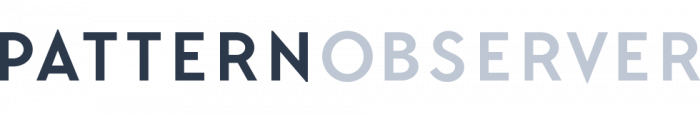

The collection was aimed at a middle class market who could not afford a Frank Lloyd Wright designed house. However, when Wright saw the exhibition that accompanied the launch – his fabrics and furniture displayed in ordinary, middle class lounge rooms – he was outraged at the banality of the spaces, stating that they didn’t respect his vision. He voiced his disagreements to the director of Schumacher’s, asking for his name to be withdrawn from the exhibit, and the two men refused to speak to each other for several weeks. The line launched as planned, and the director managed to smooth things over with Wright.

Images via: (Clockwise from top left) Taliesin Line design 104 – Art Institute Chicago, Taliesin Line design 104 – Birds of Ohio, Taliesin Line design 705 – Art Institute Chicago, Taliesin Line design 706 – Art Institute Chicago

Unfortunately, the marketing campaign suffered from a lack of consistency and limited points of sale. This was made worse by the department stores who sold the furniture, fabrics and paints all on separate floors, thereby all but destroying Wright’s message of stylistic cohesion. Still, in 1956 Schumacher’s nominated the Taliesin Line as one of their most outstanding successes.